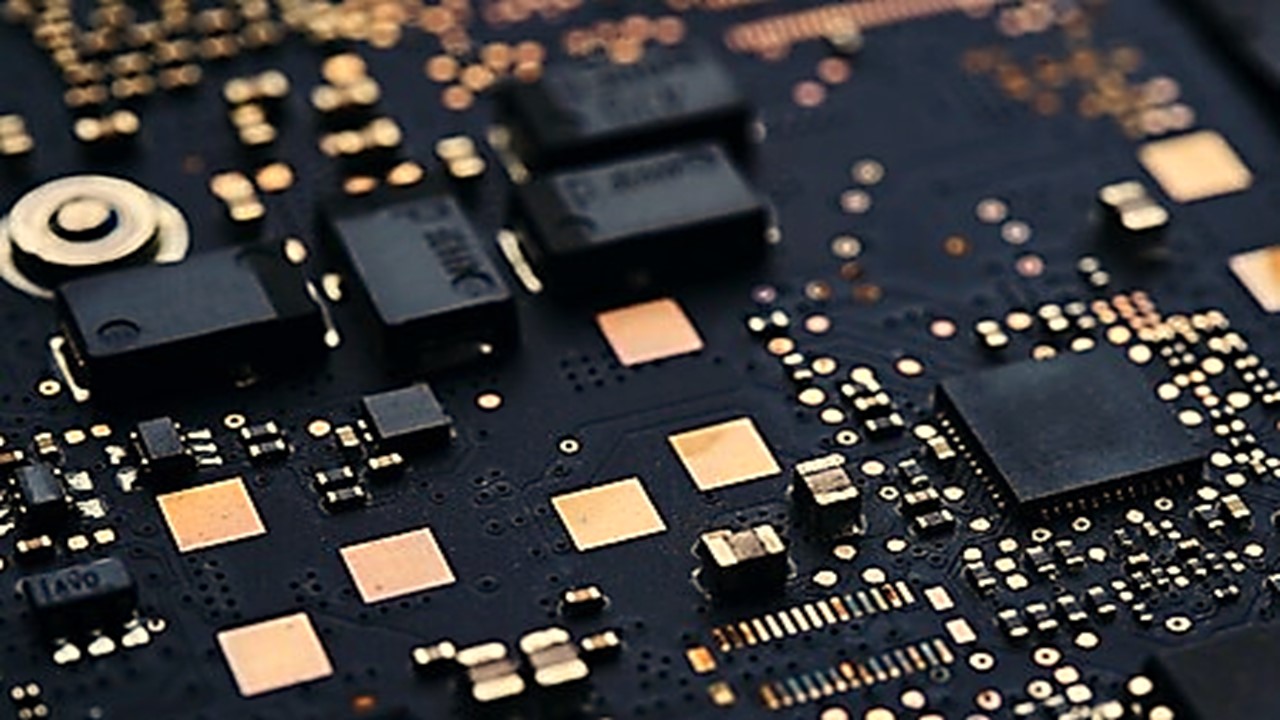

A little over a year ago I was surprised to read a story in the newspapers that went quite unnoticed: many car factories had to stop part of their production due to the shortage of chips. By now, rivers of ink have been spilled on this problem and its causes. The pandemic has affected the supply chain and has increased the demand for computers due to telecommuting. It also knocked down car sales. And all this coincided with the ban on manufacturing American chips in China, established by Donald Trump to prevent technology transfer to Chinese companies. A poisoned cocktail: when the demand for cars has increased again, the chipmakers have not been able to answer it.

Some will remember Joaquim Maria Puyal’s program on TV3 La vida en un chip, at the beginning of the 90s, when everyone was already more or less aware of the growing importance of chips in our lives and their ability to concentrate many “things” in a very small space. But what is inside a chip? And what makes them so important?

Transistors. This is the vault key of the digital revolution. The transistor is the “guilty” of the existence of computers. Based on the ability of silicon and other materials called semiconductors, it does something very simple: it has the ability to switch the electric current, which produces the zeros and ones of the binary code, which at the same time allow the logical functions that computers can perform. Very brief and simplified.

The transistor has changed our lives. The transistor was invented in 1947 replacing the tubes, which some will also remember in old radios and old televisions, which had to be heated before they worked. But it wasn’t until 1971 that the first microprocessor with 2,300 transistors was built. In 2020, 41,000 million transistors have been placed in 8 cm² of silicon. A few years after this spectacular evolution of microchips began, Moore’s law was formulated, which predicted that every 2 years the number of transistors on a chip would double. This law has been enforced very precisely and, along with manufacturing cost efficiencies, has quite simply meant that our computers and mobile phones become obsolete every 2-3 years.

Developing a European microchip industry and breaking the current Asian concentration will require huge investments and a lot of time

But let us return to the present, since the lack of microchips and the almost total dependence on the Asian market has led to the announcement of great strategies and investments from the European Union to have a European semiconductor industry.

This industry has a value chain that begins with the research phase and that requires large investments in basic science. Europe has R&D capacity through a couple of powerful centers in this field, but it is necessary to increase investment and improve collaboration between universities, laboratories, companies and public administrations.

Then there is the design of the chips, with a lot of competition between companies like Qualcomm or AMD, since a high level of specialization is required due to the introduction of electronics and software in all kinds of devices. Designing processors for a food processor is not the same as designing for a supercomputer. This segment is completely dominated by American and Asian companies.

Finally, there are the manufacturers of the chips. We have the integrated manufacturers, who also do the design and dedicate the main production capacity to their own chips. This is the case of Intel and Samsung. Manufacturers called foundries are the “pure” manufacturers who manufacture on behalf of designers, and – beware! – Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSMC) has a 60% market share. This is where the effects of the pandemic and the ban on US technology transfer contracts have become especially severe, causing the main bottleneck and global shortage.

The barriers to entry in this industry are enormous due to the very expensive technology required and the economies of scale required to deal with the high unit manufacturing costs. Therefore, developing a European microchip industry and breaking the current Asian concentration will require huge investments and a lot of time doing things right.

By the way, as predicted, Moore’s Law is coming to an end. The progressive reduction in the size of transistors has a physical limit: there comes a point where there are so few silicon atoms in the transistor that quantum phenomena appear (!) and it stops working. Does this imply the end of the evolution of computing? No! Next station: quantum computing.

Martí Casamajó, member of the Restarting Badalona association